Australian researchers have discovered how to make a special kind of diamond that is harder than the regular variety — and otherwise only found where meteorites have hit the Earth.

Australian researchers have discovered how to make a special kind of synthetic diamond that is harder than the regular variety — and otherwise only found where meteorites have hit the Earth.

The experiment, which was run by scientists from the Australian National University, compressed a special kind of amorphous carbon, which does not already have a structure.

The result was a breakthrough in creating hexagonal diamonds in a controlled setting, as opposed to the traditional cubic structure.

"There is a natural way to create [this kind of] diamond, which is harder than diamond diamond, and that is through meteorite impact," Associate Professor Jodie Bradby said.

"We found a way to make it synthetically in the lab at half the temperature that's been done before."

Dubbed 'Lonsdaleite', the unique diamond is named after pioneering British crystallographer Dame Kathleen Lonsdale.

Associate Professor Bradby's team went to the United States to use a giant x-ray machine, to see what was happening to the carbon during the compression.

"[The machine is] a big ring of x-rays going around and around, close to the speed of light," Associate Professor Bradby said.

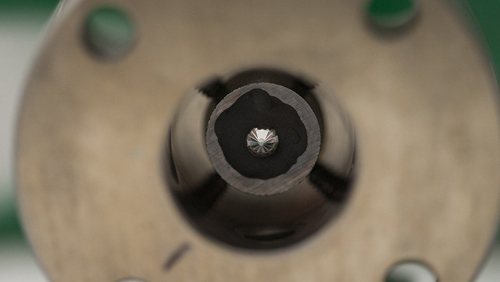

"We fired a very intense beam of this x-ray light source through a small amount of the material that is under pressures by two other normal diamonds.

"And that can tell us what's happening to that material that's being squashed under these immense pressures."

The discovery was made by a team lead by Associate Professor Bradby, including colleagues from ANU, RMIT, the University of Sydney and the United States.

For mining sites, not engagement rings

Associate Professor Bradby said they found the carbon material took on not a cubic structure like most diamonds, but a hexagonal one.

"We almost missed it actually — when we first unloaded it and looked at what happened we thought, 'oh that doesn't look very interesting'," she said.

"There was a little bump on one side of our data and we started to get very interested in this little deviation.

"We found the deviation related to a different structure of the material."

But Associate Professor Bradby said she did not expect to see hexagonal diamonds on engagement rings any time soon.

"You'll more likely find it on a mining site — but I still think that diamonds are a scientist's best friend," she said.