De Beers, the dominant diamond producer for more than a century, has spent $1bn with a joint venture partner to develop Gahcho Kué into Canada’s newest mine, hauling equipment to the site, deep in the Northwest Territories.

Gahcho Kué is found deep in the Canadian tundra where the winters are cold enough to shatter steel. But nature has left something in this hostile environment that the world finds irresistible: diamonds.

De Beers, the dominant diamond producer for more than a century, has spent $1bn with a joint venture partner to develop Gahcho Kué into Canada’s newest mine, hauling equipment to the site, deep in the Northwest Territories, during the few weeks each year when engineers can build a temporary ice road to Yellowknife, 440km away. Around the clock, trucks capable of carrying 215 tonnes haul rock from a broad pit to a vast processing plant, which crushes and sifts diamond-bearing ore and delivers rough stones into a high-security “red zone” for final sorting and shipping.

Two decades in the planning, Gahcho Kué is De Beers’ most significant bet on the long-term health of the diamond market for years — the largest new diamond mine in a decade and the company’s biggest outside its home region of Africa. Yet the first carats to emerge from Gahcho Kué come at a time of upheaval and volatility for the diamond industry — and for De Beers.

Global sales of diamond jewellery fell in 2015 for the first time in six years, declining 2 per cent to $79bn. Sales of rough diamonds fell 30 per cent. De Beers’ revenues fell by one-third and operating profits fell by more than half.

Diamonds are marketed on the idea that they will forever represent a pinnacle of luxury and materialist desire. But industry executives and business owners acknowledge that the battle for the luxury dollar is intensifying, with diamonds competing with everything from must-have consumer devices to expensive holidays. In response, the industry is looking to boost its marketing spend.

“There is no question that diamonds are losing their share of luxury spending,” says Des Kilalea, an industry analyst at RBC Capital Markets.

One concern is whether a younger generation of millennials will have the same allegiance to the products as their parents and grandparents — an allure honed by decades of marketing.

Another challenge is from synthetic or lab-grown diamonds — chemically identical to a mined diamond but created to order in weeks. Still with a minor market share, they pose multiple potential threats to the industry, as a cheaper alternative for ethically minded consumers or an imitation that erodes trust in “real” stones.

“The diamond industry is at a crossroads. There are strong forces that could lead to change,” said ABN Amro this year in a research note entitled “Nothing is Forever” — a gloomy nod to the famous phrase that has helped to sell diamonds for more than 60 years.

Bruce Cleaver, a long-time De Beers executive who took over as chief executive in May, rejects the idea that his company, or the industry as a whole, has hit an inflection point. He insists the market will improve after a cautious sales recovery this year. But he acknowledges that the sector is set to be more volatile and that the company needs to adapt as innovative competitors emerge.

“The diamond business generally has been quite slow to adapt,” he says. “People need to think very differently in the future.”

African pressures

From its 19th-century origins in South Africa, De Beers was one of the world’s most driven and successful monopolies, snapping up new mines and maintaining a stranglehold over the supply of rough diamonds, the raw material for the polished stones. But after antitrust action in the US and Europe, and diamond discoveries in regions where De Beers had little sway, its hold over the sector has loosened.

Last year the company that enjoyed a 90 per cent share of the market in the 1980s supplied just 31 per cent of global rough diamonds. Smaller rivals have built their businesses on mines or projects that De Beers sold off. At one, Botswana’s Karowe mine, Lucara Diamond last year found the biggest rough diamond in a century — 1,109 carats, which failed to sell at auction in June.

As De Beers’ influence has narrowed, the range of those with a stake in its future has widened. De Beers’ performance has become central to the future of Anglo American, the diversified miner that took control from the Oppenheimer family in a $5.1bn deal in 2011. Anglo, which raised its stake from 45 per cent to 85 per cent, has been involved with De Beers since the 1920s but has now made diamonds one of three products on which it will focus.

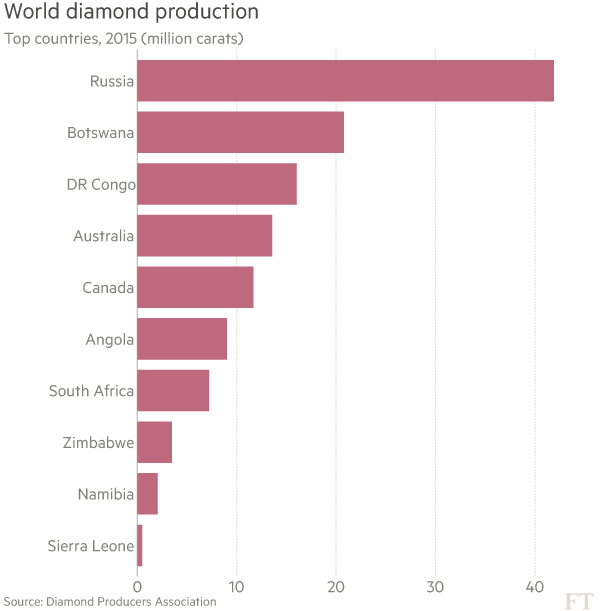

De Beers is also under increasing pressure from the countries where it mines. In 2013, the company made a landmark shift to accommodate Botswana, a 15 per cent shareholder, by moving its main sales operation there from London. De Beers faces tough negotiations over its next contract with Botswana, from 2020, and the country — the world’s largest diamond producer after Russia — exerted influence on Mr Cleaver’s appointment, preferring him to Anglo’s initial candidate, according to several people aware of the process.

Namibia, another key diamond producer, this year won its best deal from De Beers, securing the right to a greater share of diamonds from its mines for 10 years. “We are taking charge as a country,” says Obeth Kandjoze, Namibia’s mines and energy minister. “It is a transfer of power, a degree of freedom.”

The fragile midstream

Mr Cleaver is not the first De Beers chief executive to insist that the insular world of diamonds should embrace change. His predecessor, Philippe Mellier, came from the world of cars and heavy industry — an outsider chosen in 2011 to bring fresh ideas. His targets for reform included De Beers’ longstanding relationships with its customers — a group known as sightholders, who have access to the company’s vast supply of rough stones from its mines on condition that they commit to regular purchases.

This “midstream” of the diamond industry — dealers, cutters and polishers who sit between the miners and the jewellery retailers — is the most financially fragile part of the trade, especially since the global financial crisis of 2008. Margins have shrunk and banks have shunned the diamond trade, unwilling to shoulder what they perceive as its risk and lack of transparency.

Concerned by the financial weakness of some sightholders, Mr Mellier introduced requirements demanding they present internationally compliant accounts and more rigorous corporate governance. But by appearing to dismiss sightholders’ gripes about their slim profit margins, Mr Mellier, who resigned this year, irritated some dealers accustomed to a more paternalistic approach from their main supplier.

“You cannot alienate people who are spending $250m a year with you,” says an industry insider.

Shorn of credit in last year’s faltering market, De Beers’ customers staged what amounted to a buyers’ strike, forcing it into providing new levels of financial flexibility as it departed from its previous “take it or leave it” stance.

“De Beers found it cannot dictate terms to its clients any more. The dam has burst,” RBC’s Mr Kilalea says.

Mr Cleaver acknowledges the sightholders’ struggles in the past two years but says they were “grateful” for De Beers’ flexibility. The company expects periodic pressure on the midstream but Mr Cleaver insists long-term contracts with customers will stay as the core of De Beers’ sales system. “That is the way you drive demand best … We can build long-term brands in their own businesses if they have security of supply,” he says.

Marketing — or the lack of it — has been another source of concern within the diamond industry. For years the sector relied on De Beers to lead the promotional push that helped to sustain consumer demand. When the company sold most of the world’s diamonds it spent $200m a year on marketing.

But with De Beers now one of many diamond suppliers, its willingness to fund marketing for the whole industry has waned, leaving a vacuum. “This industry had a comfortable life. De Beers did everything. Now they have to pick it up themselves,” says a financier in Antwerp, where most rough diamonds are traded. De Beers’ marketing spend is down to about $120m.

A belated response emerged last year when De Beers and six other miners, representing 90 per cent of rough supply, formed the Diamond Producers Association to fund joint marketing. Its first campaign slogan launched this year, “Real is Rare”, is premised on the idea that, in a world of transient social relationships and shortlived gadgets, consumers will remain attracted by the enduring authenticity of diamonds.

Stephen Lussier, chief executive of Forevermark, De Beers’ branded diamond business and the chairman of the DPA, says the “integrity” of a natural diamond will continue to distinguish it from competitors.

This idea is epitomised by the diamonds mined at Gahcho Kué, formed in the depths of the earth half a billion years ago. De Beers points to initiatives to mitigate the effects of shifting 330m tonnes of rock over the life of the mine. It highlights partnerships with six indigenous groups and the $6bn that will go into the local economy. Canadian gems have the advantage of being free of any taint of “blood diamonds” — stones whose profits fund conflict, an accusation associated with diamonds sourced from some countries in Africa.

“Millennials are more interested in [ethical sourcing] than their parents were. That doesn’t surprise us … we can never forget the integrity of the product issue,” says Mr Cleaver.

Miners, unsurprisingly, argue that the supply and demand dynamics remain in their favour. The industry produces about 127m carats a year, about 50m less than a decade ago. There will be a rise in production as Gahcho Kué adds about 4.5m carats a year to supply and other smaller projects come online. Johan Dippenaar, chief executive of Petra Diamonds, a rival to De Beers, says the world has seen peak diamond production.

On the demand side, there are many more uncertainties. De Beers and the diamond trade are still sustained by sales in the US, the largest market. The hope is that China and India will adopt the jewellery buying habits of Americans, but De Beers assumes this will happen at a slower pace.

As for the hard-to-reach millennial demographic, Mr Cleaver says young consumers are interested in diamonds — but are still a decade away from their most affluent stage of life.

“They are not the same as their parents or their parents’ parents,” he says. “All of us in the diamond industry, in order to grow that millennial base, are going to have to think differently.”

Gahcho Kué’s opening during a soft patch in the market is not an omen for the future of the industry, he adds. “You don’t pick the exact moment a mine comes on stream … there is little doubt in my mind that over the medium to long term we will be selling into a more robust diamond market.”